THE ICE

Glaciers begin to form when snow remains in the same area year-round, where enough snow accumulates to transform into ice. Each year, new layers of snow bury and compress the previous layers. This compression forces the snow to re-crystallize, forming grains similar in size and shape to grains of sugar. Gradually the grains grow larger and the air pockets between the grains get smaller, causing the snow to slowly compact and increase in density. After about two winters, the snow turns into firn—an intermediate state between snow and glacier ice. At this point, it is about two-thirds as dense as water. Over time, larger ice crystals become so compressed that any air pockets between them are very tiny. In very old glacier ice, crystals can reach several inches in length. For most glaciers, this process takes more than a hundred years. Glacial ice often appears blue when it has become very dense. When glacier ice becomes extremely dense, the ice absorbs a small amount of red light, leaving a bluish tint in the reflected light, which is what we see. When glacier ice is white, that usually means that there are many tiny air bubbles still in the ice.

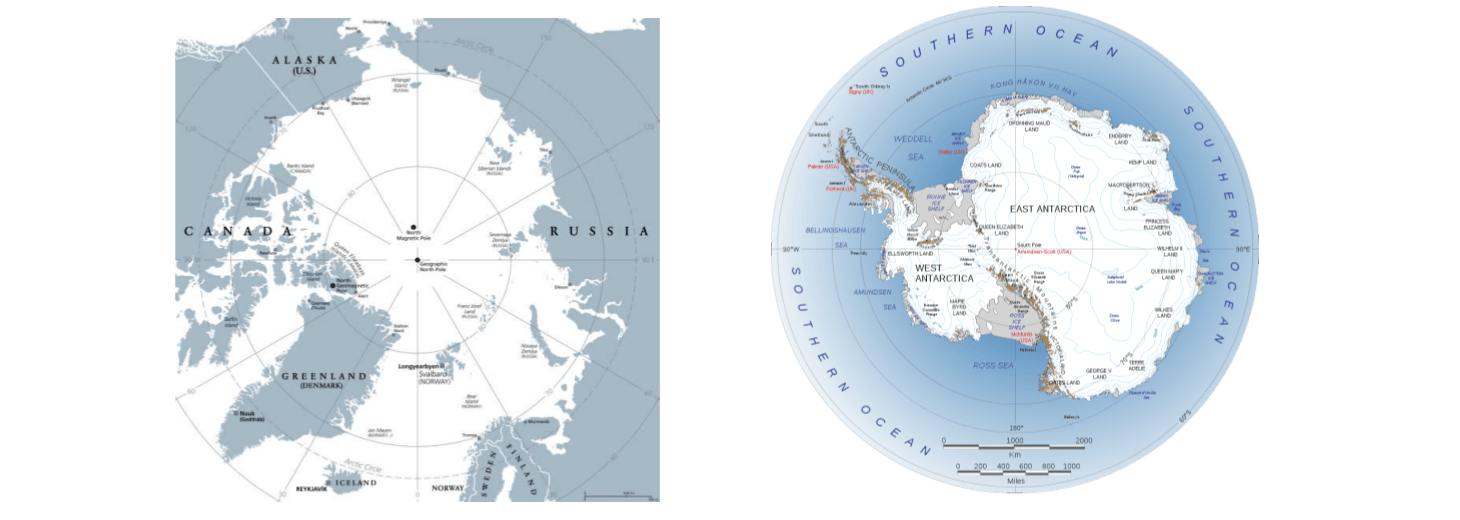

What makes glaciers unique is their ability to move. Due to sheer mass, glaciers flow like very slow rivers. Some glaciers are as small as football fields, while others grow to be dozens or even hundreds of kilometers long. Presently, glaciers occupy about 10 percent of the world’s total land area, with most located in polar regions like Antarctica, Greenland, and the Canadian Arctic. Glaciers can be thought of as remnants from the last Ice Age, when ice covered nearly 32 percent of the land, and 30 percent of the oceans. Most glaciers lie within mountain ranges that show evidence of a much greater extent during the ice ages of the past two million years, and more recent indications of retreat in the past few centuries.

Most of the world’s glaciers are found near the poles, but glaciers exist on all of the world’s continents. Glaciers require very specific climatic conditions. Most are found in regions of high snowfall in winter and cool temperatures in summer. These conditions ensure that the snow that accumulates in the winter is not lost during the summer. Such conditions typically prevail in polar and high alpine regions.The amount of precipitation, whether in the form of snowfall, freezing rain, avalanches, wind-drifted snow, is important to glacier survival. For instance, in very dry parts of Antarctica, low temperatures are ideal for glacier growth, but the small amount of net annual precipitation causes the glaciers to grow very slowly, or even to disappear due evaporation of the ice.

Glaciers melt, and ablation result from increasing temperature, evaporation, and wind scouring. Ablation is a natural and seasonal part of glacier life. As long as snow accumulation equals or is greater than melt and ablation, a glacier will remain in balance or even grow. Once winter snowfall decreases, or summer melt increases, the glacier will begin to retreat.

CLIMATE CHANGE

Presently, glaciers occupy about 10 percent of the world’s total land area, with most located in polar regions like Antarctica, Greenland, and the Canadian Arctic. Glaciers can be thought of as remnants from the last Ice Age, when ice covered nearly 32 percent of the land, and 30 percent of the oceans. Most glaciers lie within mountain ranges that show evidence of a much greater extent during the ice ages of the past two million years, and more recent indications of retreat in the past few centuries. Climatic factors strongly affect them today and during the current warmer climate, they can retreat in size at a rate easily measured on a yearly scale.

The climate, on a global scale, is always changing, although usually not at a rate fast enough for people to notice. There have been many warm periods, such as when the dinosaurs lived (about 100 million years ago) and many cold periods, such as the last ice age of about 18,000 years ago. During the last ice age much of the northern hemisphere was covered in ice and glaciers. From the 17th century to the late 19th century, the world experienced a “Little Ice Age,” when temperatures were consistently cool enough for glaciers to advance in many areas of the world. Just because water in an ice cap or glacier is not moving does not mean that it does not have a direct effect on other aspects of the water cycle and the weather. Ice is very white, and since white reflects sunlight (and thus, heat), large ice fields can determine weather patterns. Air temperatures can be higher a mile above ice caps than at the surface, and wind patterns, which affect weather systems, can be dramatic around ice-covered landscapes.

When glaciers melt, a huge amount of fresh water can be lost, which millions of people may depend upon for many activities; it supports vast ecosystems that will be endangered in drier conditions. Human activities have caused changes in the natural climate cycle, resulting in a grave environmental challenge. The release of carbon dioxide (CO2) by processes such as the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation is causing average global temperatures to rise, affecting ecosystems. In the polar regions and high mountain areas of the world temperatures are rising faster than the global average, putting those ecosystems at particular risk. Small changes in the average temperature of the planet can translate to large and potentially dangerous shifts in climate and weather. Warmer temperatures cause glaciers to melt faster than they can accumulate new snow.

Glaciers all over the world have been melting for at least the last 50 years, and the rate of melting is speeding up. Many glaciers all over the world have shrunk dramatically. We can reduce the risks we will face from climate change. By making choices that reduce greenhouse gas pollution, and preparing for the changes that are already underway, we can reduce risks from climate change. Our decisions today will shape the world our children and grandchildren will live in. We can all make a difference. The ice is melting now !

NOS MISSIONS

- 1. ALEXANDER ISLAND

2. NORTHERN ELLESMERE

3. AGASSIZ

4. SEVERNY ISLAND

- 1. ALEXANDER ISLAND

2. NORTHERN ELLESMERE

3. AGASSIZ

4. SEVERNY ISLAND

- 1. ALEXANDER ISLAND

2. NORTHERN ELLESMERE

3. AGASSIZ

4. SEVERNY ISLAND

- ALEXANDER ISLAND

2. NORTHERN ELLESMERE

3. AGASSIZ

4. SEVERNY ISLAND

Nexte Crossed